The decisions you make in the moments following a self-defense shooting will define the rest of your life.

Author’s Note: I am not a lawyer, and the following should not be considered legal advice. You should always seek the guidance of an attorney in your area, one who is conversant with the self-defense laws and the legal ramifications of the affirmative defense in court, before you make any legal decisions. There are criteria by which you might be judged in your actions, and I highly recommend that you take advantage of any courses that deal with the legalities of self-defense in your jurisdiction.

In the world of defensive shooting instruction, there is always the “what if” discussion: “What if this happens? Is it legal to shoot someone?” These kinds of hypothetical questions are a traditional part of internet gun forums, to the extent that many of them have sub-forums just for such discussions.

Even in courses devoted to self-defense law, much time is spent examining whether you may or may not legally shoot someone. How close does someone need to get before shooting is allowed? What kinds of weapons constitute a threat that would excuse shooting? Big attacker versus small one? Multiple attackers versus one? Young versus old?

Don’t get me wrong; all these questions are valid, and the answers are essential to understanding the application of law in self-defense cases. Knowing legal concepts such as the affirmative defense and its burdens on you as a defendant in court is a vital part of your defensive training.

It’s also critical you understand that shooting an attacker may very well lead to their death. While you never, ever shoot with the intent to kill, you do shoot to stop someone from killing you. Very often, the result of that fight-ending action is the attacker’s death. This reality makes the decision to use your gun a very (pardon the pun) grave one: You may end up justifiably taking the life of another human being.

Just Because You May …

From a philosophical standpoint, our laws recognize the reality that sometimes it’s necessary to shoot and possibly kill someone to save your life or the life of another innocent person. That’s the basis of the affirmative defense, which itself is the foundation for any claim of legitimate self-defense: Yes, you shot them, but you had an excusable reason for doing so.

In other words, there are situations under the law where you may shoot someone.

That doesn’t mean you always should, however. Regardless of any local requirements for you to retreat unless otherwise unable, shooting someone should be reserved for those situations where you really need to: when there is no other recourse.

That isn’t a defeatist attitude, nor am I saying that you must cower in fear. It’s an acknowledgment that shooting another human being—even a lifetime criminal who has done no good in society—will change your life. It will cost you money, time, reputation and friendships. A criminal defense might cost you hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Even if you’re cleared of criminal charges, the attacker’s family might decide to press a civil suit against you, which is a common happening in today’s world. Again, think tens of thousands of dollars at a minimum for your legal defense fees.

Shooting someone, therefore, should always be reserved for those situations where it’s necessary. How do you know it’s necessary?

In the legal portions of many self-defense classes are taught such concepts as ability, opportunity, jeopardy and preclusion—the criteria by which the use of lethal force is justified. You need to know those things ahead of time to fully understand where you’re allowed to use lethal force and where you aren’t.

That kind of legal analysis is not something you’re likely going to have time to do during an attack, however. Instead of focusing on whether you may use lethal force in the heat of action, I believe it’s better to focus on whether you need to.

It’s possible, perhaps even likely, that when you really need to shoot, there won’t be enough time to run through the legal analysis that answers the question, “May I?” Your attacker appears suddenly, you see a known and articulable threat to your life, and respond appropriately. That’s the very situation for which our laws are made: when your life is in immediate and otherwise unavoidable danger, and you must make a decision now.

Knowing ahead of time the kinds of attacks for which lethal force is appropriate, and deciding under what circumstances you would and would not shoot, will lay the groundwork for responding efficiently and appropriately.

Don’t misunderstand. You may be legally allowed to do so at that point. The totality of the circumstances may be such that, as the old saying goes, there isn’t a jury in the world that would convict you. You may have met all the legal criteria. None of that means you should exercise your trigger finger unless you need to. The question you should be asking yourself when reaching for your revolver isn’t “may I shoot this guy?” but rather “do I need to shoot this guy?” If you have time and the presence of mind to consider that question, the answer is “probably not.”

It illustrates why a class in the legalities of lethal force is so essential.

The Courtroom Downside to “May I?”

One of the problems with focusing on the “May I” rather than “Do I need to” question comes when that jury starts looking at your case. There have been court cases where someone was legally allowed to shoot their attacker (or at least believed they were legally justified), but the jury looked askance at their decision.

Focusing on the “May I?” question tends to look very much like searching for loopholes or legal technicalities to get a guilty person off. Whether that’s right or valid is a discussion for another book, but in those cases where the shoot decisions weren’t clear-cut, the defendants had a much harder time (sometimes requiring more than one trial).

As I see it, it’s a lot easier to defend the claim that “I needed to, and here’s why” than it is to defend “the law says I could, so I did.” That’s why I focus on “should” rather than “may.”

Common Misconceptions

One comment I frequently hear when talking about the legal aspects of self-defense is the idea that someone who has been involved in a “clean” or “good” shoot doesn’t have to worry because their innocence will shine through to protect them.

I have a bridge I’d like to sell you if you believe that.

The trouble is that neither you nor I, nor the investigating officers, get to decide what’s “clean” and what’s not. That’s not to say that the police can’t choose to drop an investigation due to overwhelming evidence or lack thereof—they certainly can—but not every self-defense case is absolutely clear-cut. There are many instances of legitimate defensive shootings where the evidence wasn’t unequivocal (those situations are occasionally exploited by politically motivated prosecutors).

Ultimately, it’s only the trier(s) of the facts—the jury or the judge in a bench trial—who can definitively declare your case to be clean or not. In my state, a Grand Jury makes the first decision, and if they say it isn’t “clean,” it then goes to trial, where you have the opportunity for a jury of your peers to make the final decision. At trial, someone else will be scrutinizing your acts, and you’ll be paying a lawyer a vast sum of money to present your case in a favorable light.

If you remember nothing else, remember this: what looks clean to you or me may not look that way to a person who doesn’t understand self-defense. Even if you explain it in detail, they may still not understand, especially if they’re weighing your explanation against someone else trying to convince them of the opposite.

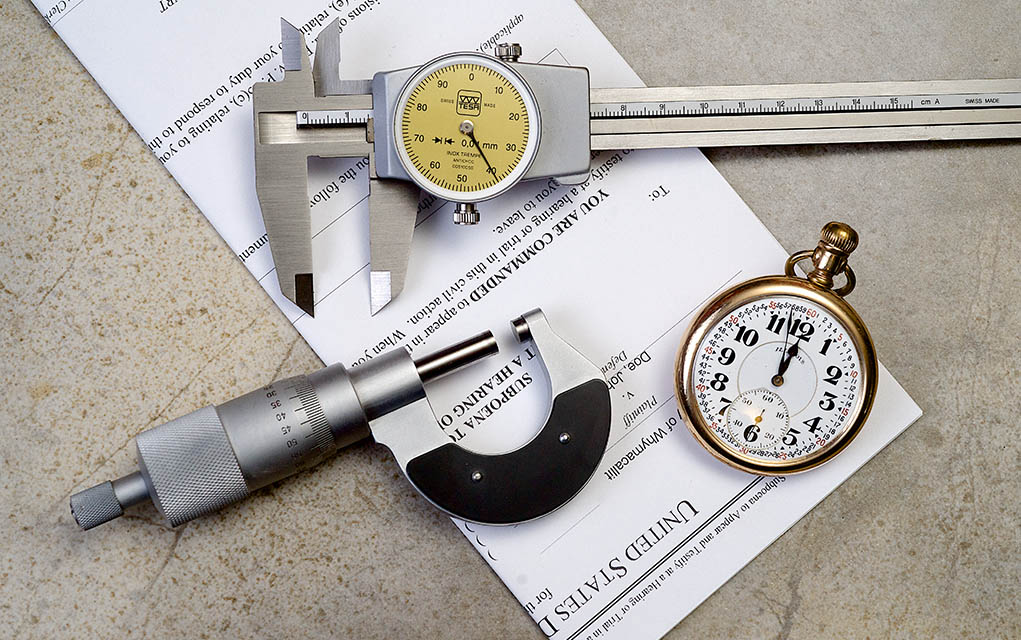

Noted defense attorney Jim Fleming was fond of saying that self-defense is determined by inches and seconds. What seems perfectly fine to you may be interpreted entirely differently by people looking at those inches and seconds in detail and with the dual luxuries of time and undivided attention.

After Your Ears Stop Ringing

After the incident, you need to articulate why you did what you did. This point is where your education in self-defense legalities becomes crucial, so you understand why the law allowed you to respond with lethal force.

Whether you shoot or not, you must make your own call into the 9-1-1 center as soon as you can. Though it’s not legal proof of innocence, investigators often take the stance that the first person to call in is the victim. This status tends to influence opinions throughout the justice system.

This maxim is particularly true in those cases where a gun was drawn and, for whatever reasons, was not fired. The bad guy gets to a phone first and says you assaulted them with a gun; minutes later, your call comes in, and you say they attacked you with a rock. Which of you is more believable at that moment?

Call 9-1-1 and describe your address and important landmarks. Then say that you need the police, that you were forced to shoot someone in self-defense, and that the attacker is down and needs medical attention. Then, describe yourself: height, weight, clothes and distinguishing features. That’s so that officers will be able to instantly identify you, the victim when they get on the scene.

When the police arrive, make sure that you’re not holding your revolver in your hand! Either holster it before they see you or put it down—cylinder open—and step away. The last thing you want is an officer to get out of their car at a shooting scene and see you holding a gun. They don’t see the halo we all believe we wear; they see a person with a gun and a body on the ground leaking bodily fluids. It’s not a situation where you want to be mistaken for the attacker.

Tell the officers that you were attacked, that you were forced to shoot in self-defense, and that you will “sign the complaint” (the legal version of “I’ll press charges”). Be sure to point out any evidence (attacker’s weapon, signs of a scuffle, indications on your person that you were assaulted, etc.) so that it isn’t missed in the investigation. (Or so that it doesn’t magically stick to an accomplice’s fingers and be taken from the scene. It happens.)

Make sure the officers know who can corroborate your story. Point out any witnesses. People tend to wander off, particularly if they’re of the “I don’t want to get involved” mentality.

Once that’s done, it’s time to exercise your right to remain silent. In other words, stop talking. Don’t give any more detail about how the incident happened or why you did what you did. Human memory is fragile, especially amid a traumatic incident, and you want to avoid saying anything that might be used against you later. You might think you’ve made an innocuous comment, which later proves to be a significant point of contention when it doesn’t precisely match the objective evidence or eyewitness testimony.

A good course of action is to say something like, “I know this is a serious situation, and you’ll have my full cooperation as soon as I’ve had a chance to speak with counsel. I’m sure you can appreciate the gravity of my position.” This is likely to be pretty close to what those same officers have been taught for those instances when they are involved in an on-duty shooting and serves as one more indication to them that you are, in fact, the innocent party.

This procedure ensures that you’ve given them the vital information they need to start their investigation while at the same time you’ve exercised (and protected) your rights against self-incrimination.

How you interact with the police after you’ve been involved in a shooting, how you articulate why you did what you did, and how well the forensic evidence is preserved will all inform the jury about whether you were justified or not. It’s in your best interest to not screw any of that up.

Use Expert Resources

I’ll repeat what I said at the top: I strongly recommend that you get appropriate instruction in the legal aftermath of defensive shootings. The premier source for training in the judicious use of lethal force is the Massad Ayoob Group, which sponsors classes all over the United States.

Famed instructor Massad Ayoob travels the country teaching what is probably the best course available on the legal issues of self-defense. Called MAG-20, you can find the schedule at massadayoobgroup.com.

(On a personal note, I consider MAG-20 to be so important that I suggest everyone who even contemplates using a gun for self-defense take the course, even before they take a “shooting course.”)

Editor’s Note: This article is an excerpt of Gun Digest’s Defensive Revolver Fundamentals, 2nd Edition.

More Knowledge For The Armed Citizen:

Read the full article here