In early September two 25-year-old outdoorsmen traveled cross country to meet in Colorado. One hopped a flight from North Carolina with an archery tag for Unit 81, which lies just north of New Mexico along the eastern flank of the San Juan Mountains. The other drove from Utah in a beat-up Subaru to hunt alongside one of his best friends.

Like so many others who’ve explored new valleys far from home, Andrew Porter and Ian Stasko were physically fit, well-prepared, and experienced in the backcountry. They hiked into the Rio Grande National Forest on Monday, Sept. 8 hungry for adventure. But on the fourth day of their eight-day hunt, they failed to check in with their loved ones at home. Andrew’s fiancée, Bridget Murphy, was starting to worry back in North Carolina. So were Andrew’s parents, Lisa and Greg Porter, who’d made their son promise to check in with them through his Garmin inReach at least once a day.

“The agreement Andrew has with us and Bridget had always been that if we didn’t hear from him after twenty-four hours, I was going to assume he was in trouble and start calling people,” says Lisa. “He’d always been great about that. So when we didn’t hear from him, I knew something wasn’t right.”

That Friday night, after touching base with Bridget and Greg, Lisa called the Conejos County Sheriff’s Office and asked them to start looking for her son and his friend. The search for Ian and Andrew would stretch on for nearly a week, expanding each day as it progressed. Conejos County Sheriff Garth Crowther says he’s never seen anything quite like it during his 46 years in local law enforcement.

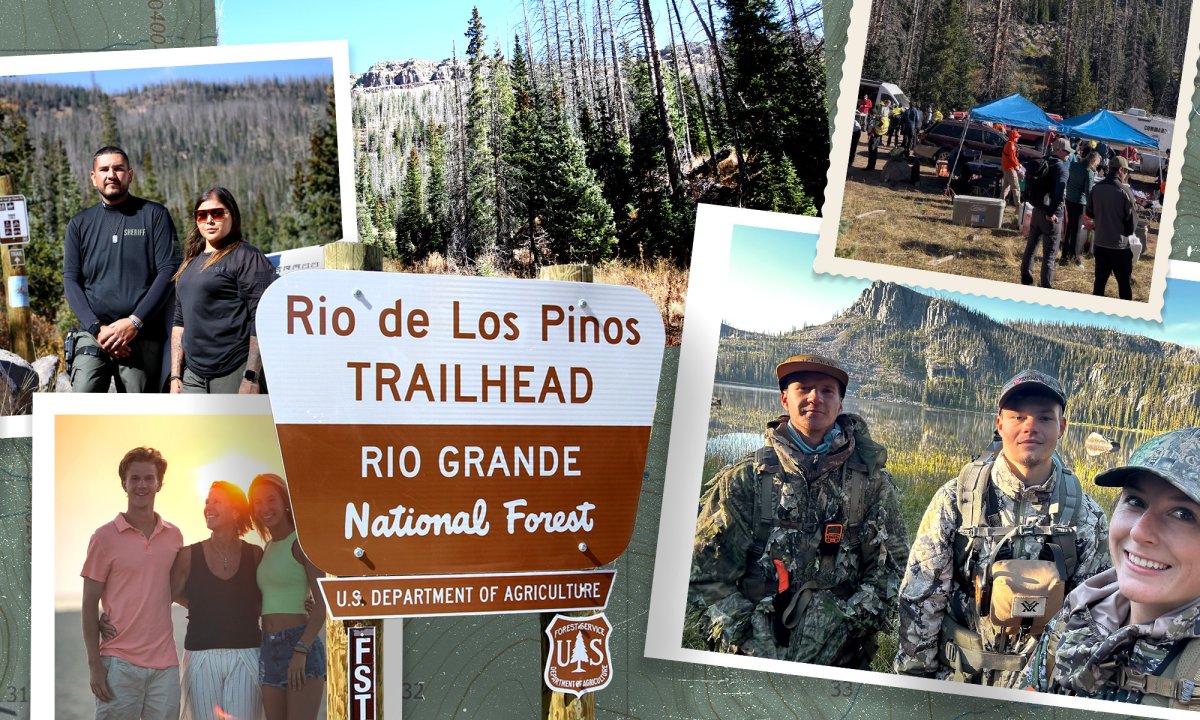

The massive effort was led by the county’s search-and-rescue crew, which is made up of around 15 to 20 deputies, firemen, and other volunteers from the community. But at the peak of the search, there were hundreds more people involved from at least 15 states. These folks joined a number of locals from Southern Colorado and Northern New Mexico, who’d left behind their own responsibilities and hunting camps to join the search party.

“I got a call from these guys in Idaho, and they’d drawn tags to bowhunt elk in this unit,” says Blake Crowther, the sheriff’s cousin and the county undersheriff. “He said, ‘My brother and I are turning our tags in. Where do you want us and what time?’ There were dozens of people like that, who were driving down on their own free will to help people they didn’t even know.”

Return to the Scene of the Strike

The October sky is bright blue and sunny when CCSO officers Sergeant Monica Dominguez and Deputy Joshua Salazar set out from the Los Pinos trailhead. A rutted gravel road had brought them up from Cumbres Pass to this portal into the high country, where aspens shimmer in golden waves that wash along the mountainsides. Looking west through a pine forest riddled with beetle kill, they can almost make out the Continental Divide.

From where the two officers park, it’s a short, 1.5-mile hike to where the bodies of Ian and Andrew were found. The two officers know the route; they’d walked a huge swath of this terrain three weeks prior. They parallel the creek toward the bowl of cliffs above, then break off trail to cross above a waterfall. Game trails lead them the rest of the way.

There, in a strip of pine trees near a meadow on the edge of the South San Juan Wilderness, a piece of flagging marks the last place the two young men had stood. The county coroner Richard Martin determined their cause of death was an indirect lightning strike. He says they would have died instantly, without any pain.

Scanning for clues beneath the scraggly pines, they find no burnt tree trunks or other obvious signs of a lightning strike. Martin says the burn marks on the two bodies, which were caused by electrocution, were sufficient evidence for him to draw his cause-of-death conclusion. Andrew’s inReach was also found in pieces in his pocket; it had sustained more damage than a drop or fall would have caused. But the spot itself, at just under 11,000 feet of elevation, is puzzling in a way. It’s exactly the sort of place a hunter would have sought shelter during a high-country lightning storm.

“They were on their way down to their vehicle. I just know it,” undersheriff Blake says. “And in my mind, they did what they’d been trained to do — or at least what people are supposed to do in a lightning storm. They got into a patch of trees. They weren’t under a single tree, or on a ridge, or in a low spot.”

It was sunny too, but colder, on the morning of Sept. 13, when Blake drove into the mountains to start the search on his own.

Kindred Spirits

Andrew and Ian were born and raised in Charlottesville, Virginia, where they grew up fishing, camping, and exploring the Piedmont’s waters and backwoods. They played Little League together and graduated from the same high school, and they both attended college at James Madison University. That’s where their friendship cemented.

“Ian was just a leader, an initiator of adventures. And he was always an adrenaline junkie,” says Missy Sirch, Ian’s mom. “He started out climbing trees, and then moved on to other things he wasn’t supposed to be climbing.”

That included the stadium lights at the high-school baseball fields, and the local mall, which Ian and a friend scaled for fun. (In his defense, he did tell his mom they were going to the mall.)

Dylan Stasko wasn’t at all surprised by these antics. She says her older brother’s outgoing and magnetic personality made others want to join him in the outdoors. Ian and his sister also spent time on the Carolina coast many summers and, like any real thrill-seeker with access to a beach and a fishing rod, Ian became obsessed with catching big sharks.

“There was this one time, when me and my mom had been waiting for like an hour and a half at this spot where we’d dropped him off on his paddleboard,” Dylan says. “He finally paddled up and he was sunburnt to a crisp, because he’d hooked up with this 8-foot bull shark. So he was basically getting dragged around, just holding on for dear life … and at one point, his rod snapped.

“He’d flagged down a boat [to bring him back], and by the time we saw him, the tops of his feet and thighs were purple,” Dylan laughs. “He was so pumped about it.”

By the time Ian entered JMU and joined the same fraternity as his hometown friend, Andrew was already seeing Bridget. The two had met in class during the second semester of their freshman year. For their first date in Charlottesville, the two met Andrew’s parents at the Porter’s home for dinner, then launched an old red canoe on a nearby farm pond.

“I thought it was just dreamy,” Bridget recalls. “I also thought it was kind of funny, because of how much effort he’d put into getting this big canoe down there, and we were just catching these little bass. But it was more about him [paddling] me around and just being out on the water. He was sincere. He did things with a purpose.”

It would be the first of many such outings together, as Bridget introduced Andrew to deer hunting during college. She says he was more reserved than Ian, which is part of why the two young men got along so well.

“There’d be this huge party going on at the frat house, and the two of them would be in the kitchen standing over this huge cast iron skillet. They’d be there cooking venison and potatoes, planning their next big adventure or talking about the essence of life.”

She remembers a few of those deep conversations when the three went hunting elk together in Montana’s Rattlesnake Wilderness a few years ago. After graduating in 2022, Bridget and Andrew had moved to Missoula together. They each bought their first compound bows there, and Andrew was learning all that he could about Western big-game hunting. Stasko joined the couple for his first-ever hunt that fall, in 2023. After a week of eating tag soup, he was ready for another helping.

“So, last year he came up, and they went bowhunting together in the Crazy Mountains for a full month. Ian didn’t have a tag. He was there to help Andrew scout and [hopefully] pack out a bull, which just shows the level of dedication they had to each other,” Bridget says. “They were unstoppable … I could barely keep up with them. And that’s why I didn’t go this year.”

The Search Begins

A fresh skiff of snow covered the ground when Undersheriff Blake Crowther arrived at the Rio de Los Pinos trailhead the morning of Saturday Sept. 13, the day after the hunters had been reported missing. A game warden with Colorado Parks and Wildlife had confirmed that Stasko’s Subaru was still parked in the last place Porter’s GPS unit had pinged: the trailhead parking lot, at around 10,000 feet above sea level.

Blake knew from his brief conversation with Lisa the night before that the two hunters weren’t supposed to be out until Tuesday, Sept. 16. But when he peered through the hatchback window, he saw a pile of gear still inside.

“I could see backpacks, and what looked like sleeping bags, stuff like that. And something just didn’t feel right,” he says. “It had been storming on-and-off up there since Wednesday.”

Blake hiked up and off the trail toward where he thought two hunters might go — above the creek and up into the bowl that surrounded the broken meadows. By the time he’d climbed a couple miles, though, the weather was already turning. Afternoon thunderclouds had poured over the Divide and they cracked overhead as he hiked down.

Blake’s first call was to Sheriff Garth, who was already out in the national forest for Saturday’s muzzleloader opener. Garth had been hit by the same storms Friday night, and after hearing Blake’s concerns, he quickly broke camp and drove to the station in Antonito.

Both Crowthers grew up in Conejos County, where Blake and Garth have hunted and fished “since we were peewees.” They’ve seen the San Juans in all their glory, and they’ve gotten lost in the thick of it — when fog and sleet and screaming winds make navigation all but impossible. They’ve also found and rescued plenty of people over the years.

Between the Continental Divide thru-hikers and all the other recreators who flock there, Conejos County gets hit hard with search-and-rescue calls. The sheriff’s office responded to 38 of those calls in 2024 and, as of Oct. 7, another 31 so far this year.

“This summer has been terrible,” says Garth. “And now it’s rifle season we’re dreading. Because people are on edge after all this, and I guarantee you that if someone is five or ten minutes late coming home, we’re gonna be getting a call.”

In a typical search situation, Garth explains, he and Blake can usually sort it themselves, or with the help of the local SAR team and maybe a single helicopter. By the evening of the second day, though, the two officers knew they would need more help.

Final Messages

Greg and Lisa Porter say their son had a quiet and gentle charm about him that drew others in. Andrew was also a craftsman. During the pandemic, he spent his lockdown at home building a cabin in his parents’ backyard.

“He had just the kindest soul, and he was so easy to get along with,” Lisa says. “So even though he was very quiet, I think people just naturally gravitated toward him because he was so approachable.”

Andrew and his twin brother, Ryan, were born to move. Lisa says they were climbing out of their cribs by the time they were 13 months old. As they matured, along with their older brother, Matthew, they threw themselves into traditional sports, but Andrew always seemed more drawn to outdoor adventures.

Discovering hunting with Bridget only fueled his fire, especially during their time together in Montana, when she was attending grad school. And while he never killed an elk with his bow, it wasn’t for a lack of trying. Bridget remembers one fall where they hunted every single day of rifle deer season, and he finally tagged a buck on the last evening. He told her it would be his last harvest with a gun — he was going all-in on bowhunting.

“We went trout fishing up there in the Yaak Valley together during the summer of 2024,” says Greg. “But as we were fishing, he kept wanting to check out these meadows — he’d run up a mountain just to see what was up there and look for sign. So, I was kind of laughing at him. I said, ‘Are you out here scouting? Or are you fishing?’ … And he said to me, ‘I just love being out here. This is what I live for.’”

By spring 2025, Andrew and Bridget had moved to Asheville, North Carolina, to continue building a life together. They bought their first house there and planned to marry in May 2026. For obvious reasons, a fall wedding was out of the question.

Before accepting his new job as a project manager for a home builder, however, Andrew had told his boss he planned to take a good chunk of September off to bowhunt elk out West. He had drawn a Colorado nonresident archery tag in April, and began planning his hunt. He knew Ian would be game before he even asked.

If Andrew was the planner in their friendship, Ian was the philosopher. Dylan says her brother was constantly thinking and talking about this idea of collective consciousness — the shared beliefs and perspectives that help unify society.

“He wanted to change the world,” says his mom, Missy. “His capstone [in college] was how to find solutions to the climate crisis by changing the world’s conscious evolution. He was continuing to work on that idea, and doing a lot of writing, when he was out in Utah.”

Holding a day job and saving money were more secondary concerns, Missy jokes. That is, until Ian’s truck broke down a week before his elk hunt with Andrew. Instead of fixing the pickup, he found an old Subaru with a failing transmission and paid $1,400 for it. Missy says that car “probably should not have made it to Colorado.”

But the Subaru did — all the way to the Los Pinos trailhead. Bridget got a text sent from Andrew’s inReach late on Sept. 7: “Made it to the end of the road.”

After spending a night near the clunker, Andrew and Ian hiked into the basin above, where they pitched camp and hunted for a few days. Andrew was even able to FaceTime Murphy briefly a few days before he died, while they were glassing from a ridge.

“The call was only 59 seconds, so it wasn’t really a conversation,” Bridget says. “But I’m so glad we had it, because I could tell how happy he was with Ian up there. He was smiling, and I could hear Ian in the background, and at one point he said, ‘I want to show you this.’ He flipped the camera around, and it was this big, beautiful meadow on top of a mountain.”

Bridget continued to get daily updates. But on the afternoon Sept. 11, she and Lisa received what would be Andrew’s final messages. He said they’d gotten soaked by storms and were headed back to the car to dry out their gear. He also let Bridget know they’d found a herd of elk and had a close encounter. The two buddies were feeling more confident than ever that they would kill a bull.

Bridget thinks the two hunters slept in the Subaru that night. Search crews would later learn that the two bumped into other hunters a nearby trailhead Friday morning. Andrew and Ian told the hunters about the elk they’d seen near Los Pinos, and they were back at that same trailhead by the afternoon.

“I think they just went out for an afternoon hunt, which is what we’d done together before,” Bridget says about that fateful day in the mountains. “They’d seen a herd, we know that. And they would have left all of their heavy stuff, and just taken what they needed to shoot a bull and bring back the first load of meat. And then I guess the storm came in.”

Historical weather data for the region shows that a series of thunderstorms hit the eastern San Juans sometime around 3 p.m. Friday. The storms brought heavy winds, rain that turned to snow overnight, and lightning.

The Search Grows … and Grows

Lisa flew to Denver on Sept. 13 and met Bridget and Greg, who flew in early the next morning. They drove south to the trailhead, which had turned into incident command headquarters. Dylan and Missy Stasko, who hadn’t been getting Andrew’s inReach messages and weren’t as in the loop during the hunt, started traveling Monday and arrived early Sept. 16.

By then, the sheriff’s office had tapped the New Mexico State Police search-and-rescue teams, along with crews from La Plata County, Colorado Parks and Wildlife, and the Forest Service. These agencies brought horse teams, dog teams, and drones, and they joined forces with local outfitters and guides, who’d brought up their own horses to help. Small businesses from the closest towns of Chama and Antonito delivered food and water in shifts.

“Just the way that people were supporting us, and the love and generosity, it was incredible,” says Missy. A family in Chama insisted that she, Dylan, and Ian’s two roommates stay at their home during the week of the search, and the family fed them dinner each night. “For me, with everything going on in the world right now, it was this beautiful demonstration of humanity, of people just being there for one another.”

The search crews spent each day combing a 5-mile radius around the trailhead as helicopters and planes flew overhead. They walked through deadfall, up drainages, and over scree through some of Colorado’s roughest country. But the hardest part, according to local law enforcement, was having to hang it up each evening.

“Our shortest day was 14 hours, and most were 18-hour days,” says Garth. “But it was the same feeling every night, and we kept saying to ourselves, ‘What more can we do? We gotta find these boys.’ That stress wears you out much faster than the physical part of climbing mountains.”

Bridget was also moved by the locals’ response. But the clock was still ticking by the end of the day on Sept. 15, and she felt like they needed more help. So she logged onto Facebook and made a post: “URGENT PLEA FOR PEOPLE ON FOOT IN SEARCH.”

“I just thought it could do something. I did not expect it to take off as much as it did, or as fast as it did.”

Bridget’s cry for help resonated, and the post caught fire, especially on several hunting pages. By the next morning, Tuesday Sept.16, there were additional cars at the trailhead, all driven by people who’d seen Bridget’s post. She then made a follow-up post, offering a $10,000 reward, and by that Wednesday, the place was packed. (Very few people who turned up ever asked about or mentioned the monetary reward.) A private pilot from Wyoming had brought his helicopter down, and a group with a mule team had driven from Texas, fueled entirely by local church donations — just a couple examples of the overwhelming response they received. The sheriff says they almost had too much help at times.

“We kept saying to ourselves, ‘What more can we do? We gotta find these boys.’ That stress wears you out much faster than the physical part of climbing mountains.”

“It was beyond belief,” adds Blake, who estimates that around a third of the volunteers were spurred by Murphy’s posts. “I have lists and lists of people, agencies, and private companies who came out. That’s not mentioning the people we had in reserve … and I wish I could thank them all individually. Everyone, from the solo person who showed up to the ten-man teams, was important.”

But even with all the horses and hounds, and the high-tech drones and choppers, crews spent five long days and sleepless nights desperate for a development. The sheriff and undersheriff, meanwhile, were putting immense pressure on themselves to bring the families an answer.

“You always try to keep that faith, but it affects you seeing them hurt, and their hopes getting thinner and thinner,” Garth says. “And the two of us, me and Blake, we have sons around that same age. They’re always hunting, always out here in the mountains. You look at all that and realize: These could have just as easily been our own boys.”

A Sliver of Peace

Thursday morning — now a full week since Andrew’s last inReach message — broke calm and clear, with even more activity at the trailhead. The Colorado Search and Rescue Association had brought more resources from around the state, and Garth was now having to hold volunteers back just to keep everyone safe. There were more than 140 people out looking in the forest that day, along with dozens more at incident command trying to keep the search organized.

“The mornings and the evening were the worst. I’d be trying to take a hot shower, and knowing that they couldn’t, that they could be out there freezing in the woods … I just felt so helpless, and our minds were our own worst enemies, coming up with every scenario possible,” says Bridget. “But at the same time, it was heartbreakingly beautiful. Seeing all these good people coming together to get them home.”

A team of CORSAR professionals intermixed with civilians were the ones who finally ended the search. They’d been assigned a new chunk of terrain on the far side of a ridgeline, so the team took the most direct and steepest route out of the creek toward the ridge above. There among the pines, they stumbled upon the two camouflaged bodies in the grass.

Blake would realize that night after looking over his own GPS tracks that he’d walked within 125 yards of the bodies on Saturday, the first day of the search. Sgt. Dominguez had walked within 52 yards of them. And for several days, until the cause of death was announced as lightning, Dominguez was distraught. She thought she’d missed her opportunity to rescue the men.

When people are dealing with unexpected or traumatic circumstances, well-meaning supporters often talk about finding “closure.” But Andrew and Ian’s families say there is really no such thing when the body of someone you love is brought out of the woods.

Bringing them home, at least, gave the families a “sliver of peace,” Bridget says. The cause of death announcement also squashed the baseless theories that had been floated in previous days by online commenters: that Porter and Stasko were somehow unprepared or unable to survive the conditions they faced.

“I guess it made us realize that they didn’t do anything wrong,” Lisa says. “They were just tragically unlucky.”

Dylan, too, says the fact that Ian and Andrew were struck by lightning raises a whole different set of existential questions about how they were taken and why. Questions that her older brother might have liked to chew on.

“[Ian] was always fascinated by entropy, and just the randomness of the universe. So it feels extremely ironic at the same time,” she says. “We were also thinking about the fact that they’d been dead for six days, and they still brought all these people together who were focused on a common goal. That was the thing he had always envisioned, this idea of collecting people’s consciousness.”

Read the full article here