This story, “When Grizzlies Ruled California” appeared in the November 1984 issue of Outdoor Life. You can read about the modern restoration of grizzlies in the Lower 48 (though not in California) in the decades since this story was written here.

On that day in 1853, U.S. Army Col. William Butts was ready to leave for San Francisco on the first leg of a journey to the East when his ranch hand rushed in to report that he had just shot but not killed the old grizzly bear suspected of taking livestock. There really wasn’t time to go chasing off after a grizzly, but the colonel reasoned that, because the bear was badly wounded, finishing the job should take only a short time. That was his first error of the day. The truth was that Col. Bill Butts never could resist the opportunity to kill a grizzly.

Stories he heard about the grizzly bears were one of his reasons for moving to California. After his years of military service in Mexico and on the Plains, life back in Missouri promised to be too dull for a red-blooded outdoorsman. Butts, a quiet man of medium build, was described as “a daring spirit who always courted danger and sought adventure.” These qualities prompted the colonel to move on to California and become a lawyer, rancher, and grizzly hunter.

Minutes after he heard the report of the old she bear, Col. Butts had gathered up his gun and long knife, mounted his favorite horse, and ridden off to dispatch the old grizzly. The trail soon brought him and his ranch hand to the edge of a ravine with near-vertical walls. The colonel dismounted and stood. rifle in hand, studying the heavy brush at the bottom of the gully, no doubt thinking that he was looking down upon exactly the kind of cover in which grizzly bears prefer to hide. As he stood on the edge of the ravine searching the thicket below for the bear, he felt the earth beneath his feet shift. Before he could move. the bank gave way and he went rolling and tumbling all the way to the bottom and the very edge of the heavy vegetation.

The bear mauled and shook the colonel senseless, then left him for dead only to glance back over her shoulder and find him looking her in the eye again, whereupon she rushed back and mauled him some more.

After he stopped rolling, Butts wasted no time starting back up the steep incline. He knew grizzly bears well enough to expect this one to be at his heels and, glancing over his shoulder, he saw the furious bear scrambling for purchase in the soft earth as she heaved her hulk up the slope behind him.

The race to the top was a dead heat and, as they pulled themselves onto the plateau, the colonel wheeled to shoot the bear. In that instant, she clamped the barrel of his 90 gun in her mouth and, according to the account given to a reporter for Harper’s Magazine, bit it so hard that she bent it “like a leaden rod.” It seems more likely that the gun simply failed to fire.

Butts raised the gun above his head and brought it thudding down upon her skull. The grizzly countered by grabbing the colonel’s left leg and pulling it into her mouth. This brought man and bear to earth, each one taking a firm grip on the other, and they slipped back over the edge of the ravine and tumbled to the bottom again.

The action was furious. The bear mauled and shook the colonel senseless, then left him for dead only to glance back over her shoulder and find him looking her in the eye again, whereupon she rushed back and mauled him some more. This apparently happened a number of times: The bear was willing to practice until she got it right. Meanwhile, the colonel was working on her with his hunting knife, the only weapon he still possessed. He carved out one of the bear’s eyes and stabbed and ripped her repeatedly until both bear and hunter were soaked with the grizzly’s blood. After half an hour of combat, during which she even took Butts’ head into her jaws and chewed on his scalp, the grizzly fell dead of multiple wounds.

Butts was not much better off. His hand-to-hand battle with the grizzly had cost him an ear and part of his scalp. His face was paralyzed on one side and he had a lifelong limp. Besides, he missed a trip to the East.

Blessed with a pleasant climate and productive soil, the California land supported a fine population of wildlife, including perhaps as large a concentration of grizzly bears as existed anywhere on the continent. One authority on the California grizzly bear, the late Tracy I. Storer of the University of California at Davis, in his book, California Grizzly, authored with Lloyd P. Trevis Jr., estimated that there were once 10,000 of the giant bears in the state. Furthermore, the California bears were among the largest of the grizzlies and, according to some people, they had the meanest tempers. Exactly how large the California grizzly bear grew is difficult to determine at this late date because most of the weights mentioned in old records were estimates. Storer and Trevis, after searching all the old documents they could find. believed that the grizzly bears of that state sometimes reached weights greater than 1,200 pounds.

From their earliest exposure to the giant bears, the frontier people decided that the bears must go. Ranchers saw them as mortal enemies of their livestock. Whether a grizzly caused any damage or not, it was condemned because it was big, strong, and physically and mentally capable of causing harm. If a bear came upon a dead animal and left a footprint as it partook of carrion, the rancher blamed it for making the kill. But, doubtless, the grizzly did sometimes vary its diet of berries and mice with an occasional feast of beef or mutton, and sometimes developed an unforgivable taste for domestic animals.

These reasons, however, were only part of the big bear’s adversary status. As long as the bears lasted, they were pursued — sometimes for meat and oil, and for the protection of livestock — but more often for the chase. The Plains Indian warrior responded to the same atavistic drive when he fashioned the claws of the conquered grizzly into a necklace and wore it as the ultimate symbol of human bravery. This frontier attitude is easily deplored by some. But times and attitudes have surely changed. The modern hunter is among the first to come to the defense of endangered game species and, today, there is research to help us understand wildlife populations and there are regulations to control the numbers of game animals that can be legally taken. Modern game management, however, came along too late to help the grizzly bear in most of its range.

The number of grizzly bears seems to be declining in much of the animal’s remaining Lower 48 range. The exception may be the northwest corner of Montana. In this section, the grizzly bear is still legally hunted. The only place where there is an open season in the Lower 48 is the Bob Marshall/Scapegoat Wilderness complex where an average of 11 grizzlies a year have been taken by hunters since 1975. Montana limits the take, depending on how many are lost to all other causes, aiming at a total mortality of 25 grizzlies, and the biologists feel that the bear is safe under this system.

Nowhere was the campaign against the grizzly more bizarre and determined than in California.

By the time there was widespread concern about the future of the grizzly bear, its fate was sealed in state after state throughout the West. Records passed down to us from those critical mid-1800 years of mortal conflict between white men and grizzly bears in California reveal some of the attitudes that threatened the big bear everywhere, and offer clues that might help us adjust our thinking about wildlife in general. Nowhere was the campaign against the grizzly more bizarre and determined than in California.

The most unusual brand of bear destruction ever practiced in California or anywhere else was introduced by early Spanish colonists. On special religious holidays, they staged fiestas that included fights between the most-powerful bulls available and the biggest grizzly bears to be found.

Although the spectacles varied in detail, the bear was typically held in a strong cage made of logs and iron until the time came for its release into the arena amid loud cheering from the crowd. The attendants then prodded a short-tempered range bull, wild-eyed, with long pointed horns, into the ring.

The bear was sometimes shackled to a chain perhaps 20 feet long while the bull was unfettered. A strong bear, and some were said to weigh nearly a ton, usually held the advantage, but there were bets on both the bull and the bear. The fights were ugly affairs, degrading to the animals and the people alike.

The real excitement, however, came to a select minority of horsemen. A day or two before the fight, they went off to search for the largest, fiercest grizzly bear they could find. Their task was to bring the bear in unharmed.

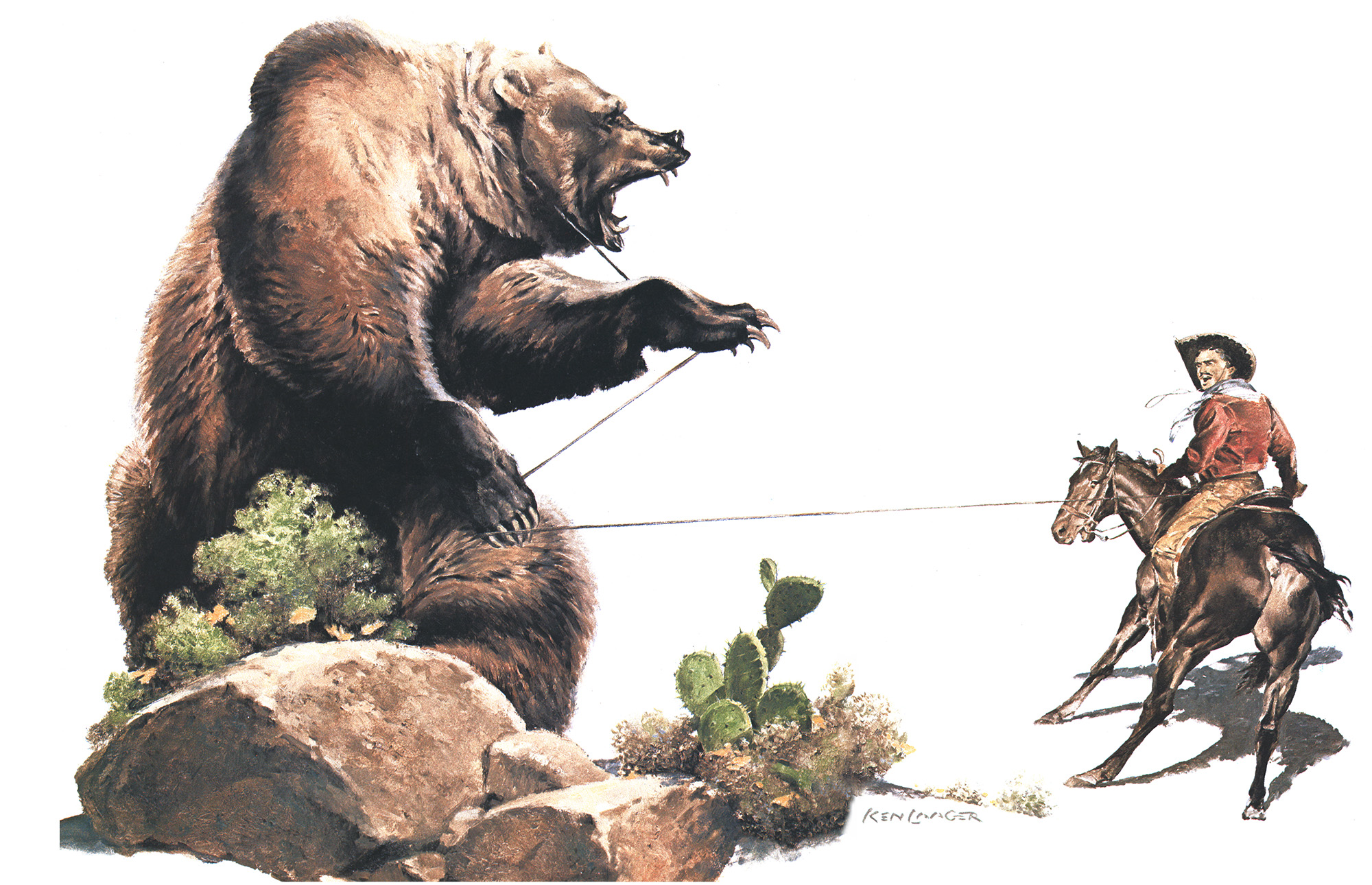

This risky business called for the skills of a team of four of the best and most daring horsemen and ropers in the community. The four lazadores, dressed in all their finery, rode off to search out a bear, preferably a giant. They used only their lariats, fashioned from tightly braided strips of cowhide. Frequently, the roping of grizzly bears was done at night when the bears were out in the open feeding. In the daytime, the chaparral thickets were the best places to find the beasts hut were poor places to rope them. The target for the first man’s lariat was one of the bear’s front feet, and the next target for another member of the team was the other front foot. With the highly trained horses pulling in opposite directions, the bear was stretched out.

Then came the riskiest part. With the horses holding the struggling bear as best they could, one of the riders slid from his horse and approached the furious bear. He slipped a loop around the bear jaws and tied them shut. Next, he cautiously dropped a loop around one of the front paws and bound it and its mate together tightly. Finally, the hind feet were also trussed. The mighty grizzly was now helpless and ready for the trip back to the settlement.

Some learned the hard way not to throw a noose around any part of a bear.

This was the work of heroes and the idea was certain to spread inland to the Plains where the American cowboy’s reaction was predictable. The cowboy, good with his lariat and willing to admit it, roped many a grizzly bear for the hell of it. But the ropes were used simply to hold the bear in place and keep it harmless while it was dispatched with a gun or knife, depending on how close the cowboy was willing to come to the bear and how much he wanted to talk about the episode at the Dry Gulch Saloon the next time he got to town.

Some learned the hard way not to throw a noose around any part of a bear except the feet. A California grizzly bear once taught this lesson to a young naval officer who came out West for the express purpose of lassoing a grizzly. The incident is described in the 1866 book, Border Reminiscences, by R.B. Marcy, a career U.S. Army officer, Western explorer, and map maker.

The young naval officer practiced until he was proficient with rope and horse. Then he hired a guide, and set off into the California mountains in search of his bear. He soon located one that qualified as a giant among grizzlies and set to work to reduce the beast to possession — or so he intended.

As the bear chaser rode down on the grizzly, lariat whistling in lazy overhead circles, the old bear suddenly stopped, turned, and stood up on its hind legs. The rope fell gently over the bear’s head and was promptly jerked taut by horse and rider. The animal sat down solidly on its haunches.

At this point, the bear was supposed to tumble over into a heap, after which he would be led away by the proud horseman. The grizzly didn’t know the script, however, and sat there like a giant anchor. Then it noticed that it was choking and traced the cause to the rope around its furry neck.

The bear’s response was to begin pulling horse and rider to him, paw over paw. The great bear shortened the distance until the rider realized that the situation was serious and yelled to his guide to save him. The guide dashed in at top speed, slashed the lasso, and both horses carried their riders to safety at record speeds. The guide said that he was willing to search for a smaller, more manageable bear but the Easterner concluded that he should adopt some other hobby.

The same stunt was tried with a more serious outcome one fine day in 1850 in Sonoma County, California, by ranch hand Jim Boggs’ partner, John Richards, who fancied himself handy with the rope. Boggs saw his friend’s lasso settle around the bear’s paunch and then watched with disbelief as the old bear seated himself upon the earth and began handlining his catch. The problem was intensified by the fact that the rope was securely knotted to the saddle. The horse was no dummy and somehow pulled free of the saddle and raced off toward the corral. leaving its rider at ground level in confrontation with a furious grizzly bear that set to crunching and clawing all human parts within reach.

Boggs, now deciding to rescue his partner, marched up to the bear, placed his cocked handgun against the animal’s head and pulled the trigger.

The outcome of this incident was described in the book Reminiscences of a Ranger, written by Horace Bell, who came to California in 1842 and became a peace officer and a newspaper publisher. “The bear at once released the partner, who took to his heels, leaving Jim and the bear to tight it out.”

Boggs lodged one more bullet in the grizzly and then purposely went limp. The bear, thinking that he had done the job, lumbered off, but turned and checked just in time to sec Boggs lift his battered head to appraise the situation. The bear turned, pounced on Boggs again, and mauled him so terribly that there seemed little chance of his surviving. Although he did live, he was a lifelong cripple. His partner suffered less severe injuries and it is believed that neither Boggs nor his partner nourished any interest in roping more grizzly bears.

In those years when the Golden State still had a fair share of the grizzly bears that nature had granted it, people came for many reasons, some seeking gold, some to ranch, some for the benign climate. Occasionally, a man came who was lured most of all by the grizzly bears for which the state was famous. One of these hunters was Colin Preston, a red-bearded lawyer and’ a black-bear hunter from the hills of Arkansas who was in California by 1845. By his own accounts, the free-wheeling Preston killed an unbelievable 210 grizzlies in his first 10 years.

“They are scarcer now,” he said later.

There had once been grizzlies close to his ranch, but later he sometimes had to go 50 miles to find one.

We have a description of one of Preston’s methods from an anonymous journalist who reported on his visit to the hunter’s ranch in the mid-1850s.

Grizzlies were baited to a place where they could be shot, usually with zero danger. Preston and his ranch hand Antonio, who was also a determined bear killer, made a scent trail by tying part of a calf or deer to the saddle with a rope and dragging the bait across the fields to the base of a large oak tree. The bait was tied in the lower branches and the hunters perched in the trees above it to wait.

On one such hunt, Preston and Antonio waited three nights for the bear to come and sometimes fell asleep in the tree.

“Then,” as Preston said, “a shadow appeared, moving toward us in the direction of the drag. I spoke in a whisper to Antonio. He woke up suddenly and. losing his presence of mind, fell over forward on the ground, his rifle catching and hanging in the tree. He ascended the tree with astonishing ease.”

Preston explained at length that Antonio was a coward at heart.

The bear was drawing near when, as Preston said, “To my utter amazement, off went Antonio a second time.”

This time, Antonio bounded off into the darkness and, as the ranch hand departed, the hungry bear stood on its hind legs and reached for the bait. Preston placed the muzzle of his gun against the bear’s ear, shot, and saw the animal go down. “With the kicking of the gun and my own unsteadiness, I too rolled off the branch.” His shoulder struck the bear’s head. “Terrified now, I rolled myself off and ran — and didn’t stop until I was back at the ranch.”

Whatever the motivation, the grizzly bears that once roamed California in abundance were doomed. Many felt that their passage was inevitable as livestock spread across the states, and as cities and towns expanded. People worried about their safety, and ranchers, claiming threats to their stock, never rested until the last bear vanished. The grizzly bear’s numbers had fallen with terrible swiftness in a matter of decades, and few people ever saw a wild grizzly in California after the turn of this century.

In those years when the Golden State still had a fair share of the grizzly bears that nature had granted it, people came for many reasons, some seeking gold, some to ranch, some for the benign climate. Occasionally, a man came who was lured most of all by the grizzly bears for which the state was famous.

In view of this, the astonishment that registered on rancher Jim Agnew’s face that August day in 1922 is understandable. On his Tulare County property, Agnew came upon a large bear that looked like a grizzly at a time when all grizzlies were said to be gone. Agnew, who was concerned about the welfare of his livestock, did exactly as thousands of others had done before him. He raised his gun and brought the bear to earth. What the Spanish Californians and American frontiersmen and ranchers had worked at so relentlessly, Agnew had apparently finished. He had taken the last grizzly bear killed by the white man in California. A couple of years later, there were vague reports of another grizzly in the vicinity of Sequoia National Park. That was all. The California grizzly bear was gone.

Back-glancing and condemning Agnew’s act is easy, but a fair-minded person must admit that attitudes toward bears have changed in the last half-century. There is a new awareness that endangered species, game and non-game, must be protected. And some of the most conscientious Americans in the fight for the causes of wildlife and their habitat are this country’s hunters and fishermen.

Today, only the stories of the California grizzly remain. These stories and the static image of a great bear on the state’s flag remind us that the fabled bear is gone for good from the coastal state where it once prospered. The drama of the grizzly bear’s passing was replayed in state after state throughout the West.

Read Next: My Buddy and Our Hounds Were No Match for the Ghost-Town Grizzly of Old New Mexico

Now, the grizzly is nearly gone in the Lower 48, and new ways have developed to nibble away at the remaining population. “You wouldn’t believe all the ways they are killed,” said one grizzly bear biologist. The big bears are struck by trains and killed on the highways. They move into populated areas, get in trouble with people, and have to be destroyed. Poachers take them and sell the parts at absurdly high prices. Meanwhile, the last of the grizzly bear’s habitat is invaded by developers. In the face of all the pressures, the big bears deserve whatever help we can render if they are to avoid a reunion with their California cousins.

Read the full article here